Really Rotten Science 1: Dunbar’s Number

November 18, 2015 – 10:49 amThe field of social psychology is controversial at its core. The findings of this field are highly likely to treated as normative in the contested discussions we have about our social lives. Among the more problematic findings asserted is that which goes by the name of Dunbar’s Number, and is attributable to Robin Dunbar, of Oxford University.

At the heart of the issue is a misguided correlation that appeared in a 1992 article that has since garnered over 1,200 citations: Dunbar, R. I. (1992). Neocortex size as a constraint on group size in primates. Journal of Human Evolution, 22(6), 469-493.

The correlation is between two variables. In the X-corner we have “neocortex volume” as measured in 38 primate genera (not including humans). This is explicitly justified as an index of “cognitive capacity”, which is not a term with any widely agreed meaning. In the Y-corner, we have “group size” based on ethological observation. This yields a scatter plot, and when the data are log transformed, a fairly strong correlation between the two variables is found. Then, in a manner that I argue is entirely indefensible, humans are added to the plot based on their cortical volume, and we can use the linear fit to observe a calculated group size for humans of about 150. This is Dunbar’s Number. Although no normative conclusions are drawn in the original study suggesting that humans “ought” to live in groups of about 150, much of the subsequent discussion of this has been tinged with the romantic idea that there is a “natural” or “correct” group size for humans to live in, or to maintain through their social interactions.

Let’s consider this work in detail. The X-variable comes first. Neocortical volume is taken as an index of cognitive capacity. There is no scientific basis for this choice, as cognitive capacity is not a well defined kind of thing. This variable is chosen in advance, and is used as a lens through which to view other animals. If you were to choose one anatomical characteristic of homo sapiens that really stands out, it is our neocortical volume, which is grossly inflated by the size of our frontal lobes. Many animals have something special about them. Giraffes have long necks, cheetahs are really fast runners, and humans have very big forebrains. Figure 7 of the original paper makes this very clear: humans are not typical when viewed through the lens of neocortex volume. Imagine, if you will, some giraffe scientists deciding that neck length was an appropriate variable with which to study other animals, and would measure neck length in many non-giraffe animals, and then add giraffes to the plot. Lo and behold, giraffes would be spectacular. This is not an innocent variable. For a wonderful critique of this kind of anthropocentric wishful thinking, I would point to Louise Barrett’s recent article “Why brains are not computers, why behaviourism is not Satanism, and why dolphins are not aquatic apes”. ( The Behavior Analyst, 1-15., 2015), ( or see the poem by Ambrose Bierce at the foot of this page).

Now let’s look at the second variable, group size. This is motivated by a view of social interaction in which each member of a group is involved in information processing to keep track of the others. This is a venerable, though highly contested, position one can take with respect to social interactions. However, group size is really complex, and will be influenced by many factors, and not in a simple way. Orang Utans give pause for thought here. They are excluded from the analysis, justified due to the unavailability of data on neocortex size. These close relatives live relatively isolated lives some of the time, come together some of the time, and generally make it difficult to claim that they have one group size or another. Discussing this, Dunbar considers the possibility that they are “socially degenerate”, and then does some hand waving to suggest that they might have unseen group sizes of 6 to 15 individuals (despite explicitly noting that most studies have concluded that there is no simple group size for the species).

Another example of carving the data to fit the hypothesis is clear in discussion of Miopithecus, where prior work asserted that group sizes were larger in populations living commensally with humans, and so “therefore only groups listed by Gautier-Hion (1971) as living in undisturbed habitats were used when calculating the mean in this case”. What just happened? Data was sliced and diced in order to shore up a romantic notion of nature as separate from man, and only undisturbed habitats are considered informative. This presupposes that humans are not part of nature, and that animals become corrupt in our presence. This is entirely anthropocentric, and is beholden to the problematic assumption that humans lie outside the order of nature, and not within it.

But then things go very wrong indeed. In a 1993 paper (Dunbar, R. I. (1993). Coevolution of neocortical size, group size and language in humans. Behavioral and brain sciences, 16(04), 681-694. cited 1,600+ times), Dunbar takes this seriously compromised correlation and applies it to humans, based on their neocortical volume, allowing him to produce Dunbar’s Number, the number of humans that we have (do, should, used to have?) in our social groups. Now here I have a slight problem. Using Dunbar’s data from the 1991 paper, I get a different regression equation than him. The number he comes up with is 147, where I get a paltry 100. But it is not worth chasing down the difference because this kind of extrapolation is absolutely not justified. It is not allowed. It breaks the rules of the game. Humans, as we and Dunbar have noted, are off the scale when it comes to our big forebrains. In the 1993 paper, he notes that the value for humans is 30% larger than that for any other primate.

Here is a basic rule in correlational studies: correlations are based on the tentative assumption that the relationship between the variables is linear. This is generally not true for any naturally occurring variables, but may be true within restricted ranges. For example, there is, for any spring, a range of forces we can apply where we will observe roughly linear increase in length with increase in force. But outside that range, things are not clear. Springs will break. Complex relationships such as the one dreamed up here are guaranteed not to have a simple linear form. So, all other things being equal, if we establish a correlation over the range [X_low . . . X_high], we might argue that we can use this linear relationship to make predictions for unseen cases where the predictor lies within the range which we used to establish the correlation. We have absolutely no license to extrapolate beyond that range. We cannot make predictions based on a linear relationship except within the range where that relationship holds. This observation is entirely distinct from the other objections raised above.

Dunbar has this to say: “Strictly speaking, of course, extrapolation from regression equations beyond the range of the X-variable values on which they are based is frowned on. We can justify doing so in this case, however, on the grounds that our concern at this stage is exploratory rather than explanatory.” This is simply wrong. You cannot so justify things like that. The human data point is way, way off the scale.

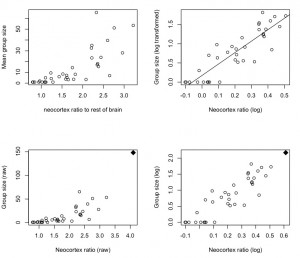

Click to embiggen

In these plots, the left hand column shows the raw data (group size, ratio of neocortex to rest-of-brain). On the right hand side are the log transformed values (the log transform is needed to make the relationship approximately linear). The lower two panels show how the plots look when we add in the single data point for humans – that’s that black square in the top right corner. The human point is not justified here because of “exploration”. This is not science. It should not be discussed as science.

The 1993 paper contains discussion of “group size” in humans. What could this mean? Dunbar leans on some romantic notion of primitive humans living in their close-to-nature hunter gatherer societies, which he cherry picks and opines he can discern a group size for humans (unadulterated by modernity). He tries to draw in observations about the size of military units in professional armies into the story. All the unmotivated, hand-picked examples he chooses happen to support his hypothesis that there is a right/true/natural size to human groups, given by Dunbar’s Number. There is wishful thinking a plenty here, but no science.

The 1993 paper has been followed by thousands of references, citations, and extrapolations from this nonsensical foundation. Dunbar’s number has gone down in the scientific literature as if something had been found out.

But who cares? A social psychologist (sorry, evolutionary social psychologist) decides to fancifully hallucinate a relationship between brain size and group size. Shouldn’t we just walk away and tut-tut about evolutionary just-so stories?

Emphatically no! This is normative science, and it is sold as science, which thereby carries authority. We use science to understand norms and deviations from the norms, to inform public policy, develop educational curricula, and to distinguish between the healthy and the pathological. The quality of science is a political and ethical matter, and when it comes to science about ourselves (whatever that means) such concerns must be centre stage. This specious rubbish is in that literature, polluting our view of ourselves. Dunbar’s Number is nonsense, and ought to be eradicated from any science worth having. Would that it were alone.

Normative Social Psychology? Just say NO!

Postscript: Ambrose Bierce penned the following poem in his Devil’s Dictionary of 1922:

Sorry, comments for this entry are closed at this time.